Solving performance problems using a Modern Balanced Scorecard in a Charity: The Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Fund

This case study describes the application of the modern balanced scorecard approach in a charity. The case study was developed with the support of Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Fund and published with their kind approval.

A shorter version of this article, entitled “Demonstrating and managing performance in a charity” appeared in “Trust and Foundation News”, the journal of the Association of Charitable Foundations (ACF), June 2009.

Download this case study as a pdf

Balanced scorecard charity case study for the Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Fund

The Fund’s Report and Financial Statement to their Trustee’s 2008, refers to their Balanced Scorecard:”

“How do we measure our performance?

In order to ensure the careful monitoring of performance towards the achievement of the initiatives’ objectives the fund has adopted an integrated approach to internal reporting including both financial and non-financial measures.

The “Balanced Scorecard” has been adopted for each of the initiatives as part of this integrated approach. These are primarily used for performance management at strategic (Board) level and tactical (management) level.”

Introduction – Why did the charity want a balanced scorecard?

There is a need to demonstrate effectiveness and performance across the charity sector. But how do we do it? How do we demonstrate the efficacy of our projects and activities? How do we demonstrate value to our beneficiaries? How do we demonstrate to the Trustee Board that the strategy is being executed?

The usual answer is to immediately look for ways to measure performance. At the Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Fund (the Fund), they took a more subtle approach: an approach that involved maps of their strategy and a modern, strategic, balanced scorecard.

The Fund went beyond simply attempting to measure activity and results. They moved to clearly showing what they are doing and how those activities will deliver results. Even in an innovative, lean, charity like the Fund, the techniques used and the process of developing these modern balanced scorecards has had positive effects.

Their “Strategy map and balanced scorecard” has created a more constructive dialogue with the Fund’s Board of Directors than simple measurement would have done. It helps the Fund’s managers to demonstrate how they are implementing their part of the overall strategy, despite being at different stages of implementation, with different emphasis and different benefits. In addition, it helps the Fund’s managers show how they are contributing towards the Fund’s overall strategy. And, the approach has made it easier to trace through and describe the impact of the Fund on its ultimate beneficiaries.

Introducing the approach has also provided new ways to think about, and think through, the Fund’s strategy. As a result the Fund has identified where capabilities and knowledge need development, and where its initiatives (the Fund’s teams) can help each other improve across the organisation.

The up to date, strategic balanced scorecard approach used at the Fund has potential benefits for charities across the sector. It can help planning processes be more systematic and less political. It helps internal communication of the strategy as a whole. It makes discussing scarce resources, performance and results easier. With the new Charities Act, it could even be used to communicate with Stakeholders.

This case study explains the Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Fund’s approach and the benefits the Fund has identified.

The situation at the Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Fund

The Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Fund was already demonstrating its success. The Fund focuses on three main initiatives, the Palliative Care Initiative, the Refugee and Asylum Seekers Initiative and the Partnership Initiative. Each initiative has a desired outcome and a set of strategic objectives to be achieved over a five year period. For example, objective one of the Palliative Care Initiative is; ‘An HIV/AIDS community and donors that has integrated palliative care into the continuum of care for people with HIV/AIDS and their families. The Fund’s existing Strategic Plan 2007 – 2012 already articulated the objectives for each of the Initiatives.

However, the Fund felt it could communicate its strategy and demonstrate measurable progress more effectively. The Fund decided to investigate the modern balanced scorecard approach and invited the specialist strategic balanced scorecard consultancy Excitant to help them.

Like many charities and other organisations, the Fund already had a “balanced scorecard”. Like many balanced scorecards, this was a collection of measures in various categories, or perspectives that informed the operation of the Fund. However, these measures told little of the story of the strategy. In common with many, what might be called “operational scorecards”, the measures were primarily financial and operational, with some covering staff and culture. It also tended to tell managers what had happened. While the previous scorecard was far more balanced than most financial reporting, it didn’t yet tell the story of the Fund’s strategy and how it would succeed.

At the initial briefing with Excitant, the management team explained that they wanted to be forward looking and demonstrate how the Fund’s strategy was working. They wanted something that they owned as managers and helped them communicate both inside and outside the Fund. Something that was more was useful to them as managers, than their operational measures. As one manager put it, “We don’t want the sort of over-detailed, resource intensive, micro-management scorecards that the NHS uses”. As another manager said, “I want to fall in love with the balanced scorecard.”

So it was agreed to develop a modern balanced scorecard which, as a starting point, ignored measures. Instead, Fund staff explored their strategies and developed strategy maps.

Developing the Fund’s strategic balanced scorecard

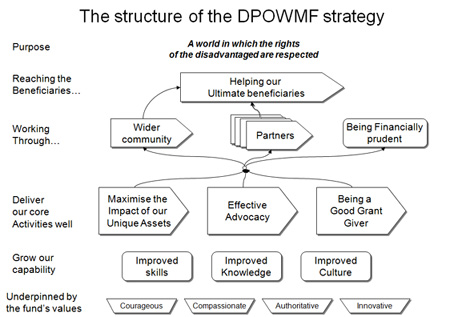

Early versions of balanced scorecards collected or developed measures in various perspectives, typically financial, customers, processes and learning and growth. Whilst this adds “balance” to the measurement of an organisation, it often becomes a process of collecting, classifying and adding extra operational measures, but does not help to address the implementation of the strategy. By 1995/6, Norton & Kaplan realised that there is a need to articulate how the strategy will make a difference to the organisation, its customers and financial results, and is therefore measured and managed. These developments are encapsulated in what are called “strategy maps” which map, and show pictorially, how the strategy will be delivered. The framework of the Fund’s strategy map is shown in figure 1.

The first development was to define objectives in each perspective. Never, ever, start with measures. Starting with measures means you end up managing only those things you believe you can measure. In contrast, starting with objectives has the advantage that you know why you are measuring any particular aspect of the organisation. You choose how best to measure what you want to manage (the objective). If a measure turns out to be a poor measure or indicator for the objective, it can be discarded and a better one found. It also makes cascading and communicating balanced scorecards far easier. Instead of forcing a measure to exist at many levels, objectives allow appropriate measures at any level of the organisation.

As can be seen from a simplified version of the Fund’s strategy map, these objectives are developed in each perspective. In the Fund’s case, the beneficiaries have objectives, the partners have objectives, and there are financial objectives. There are also objectives for the activities of the Fund and objectives for growth and development of the Fund’s capability.

This approach did cause some discussion at the Fund. In the charitable sector much effort has been put into trying to systematically measure the impact on ultimate beneficiaries. As the effects of the Fund’s interventions are often diluted and subject to many other influences and many players, it can be hard to demonstrate when particular investments and actions have actually made the difference. This is even more difficult where interventions are designed to bring about policy change or influence governments such as, for example, assessing the Fund’s role in campaigning to secure an international treaty banning cluster munitions or , in ensuring that the crucial role of palliative care is recognised by national governments in Sub-Saharan Africa. Therefore, there was some initial scepticism that we could achieve anything against this background. As one member of staff observed, “We have been trying to measure effect in the sector for 20 years and no one has really succeeded.”

Rather than starting with measures, the Fund started with the objectives of beneficiaries. The Fund explored the bigger system of policy change and intervention that it was a part of, which made explicit what the Fund was trying to achieve. The managers explained how the activities of the Fund would ultimately influence and improve the lives of people and ensure that the rights of the disadvantaged were respected. This thinking, and the set of objectives that came out of it, was captured in their detailed strategy maps.

This highlights the second important aspects of strategy maps and strategic balanced scorecards: looking at the relationships between objectives; the cause and effect relationship; the lines of influence and effect. By concentrating on the links and relationships between the objectives we can describe what will drive change. The Fund can describe how its strategy and activities should ripple through and make a difference to the lives of the ultimate beneficiaries. This is done by asking, “If this is what our beneficiaries need, what do we have to focus on to make sure we deliver that for them?” We also ask the question, “If we are to do this better as an organisation, what capabilities in the Fund do we need to improve? “.

In many ways it is the links between the objectives that matter more than the objectives themselves. If we grant these funds, to our partners, will it help them make a real difference to the ultimate beneficiaries? How do we know? Can we demonstrate it? Of course this thinking is embedded within all levels of management within the charity sector, including each of the Fund’s managers. The approach made the thinking explicit and captured it as a strategy map. This strategy map made it easy to tell the story of the strategy, on a single page. Once explained and detailed, its progress can then be seen, tracked, and managed.

Developing the Fund’s strategy maps

The simplified framework for the Fund’s strategy map is shown in figure 1. The purpose of the Fund is clearly stated at the top of the strategy map. The ultimate target for the Fund is to help the eventual beneficiaries, as captured in its mission statement. As a grant making organisation, the Fund helps its beneficiaries by giving grants to and working with selected partners, who have the capacity to deliver each initiatives’ desired outcomes. For instance, the Palliative Care Initiative wants people across Sub-Saharan Africa with life limiting illnesses, such as HIV/AIDS, to have access to palliative care that alleviates their physical pain and provides psychosocial, spiritual and bereavement support. In order to achieve this, the initiative believes medical and nursing schools need to train doctors and nurses in palliative care skills. In working towards achieving this objective, the Palliative Care Initiative with The True Colours Trust (one of the Sainsbury Family Charitable Trusts) is holding a conference in Kampala, Uganda in October 2008 aimed at the heads of medical and nursing schools from 10 Sub-Saharan Africa countries, to encourage them to incorporate palliative care into the core curricula of medical and nursing schools. The conference is being held in partnership with the African Palliative Care Association. The Palliative Care Initiative balanced scorecard reflects these partnerships.

At the same time the Fund will seek to influence the wider community: governments, the media, and the public at large, and develops advocacy and campaigning strategies to create the greatest impact possible given the inputs.

An example of this can be seen in the Fund’s membership of the Cluster Munitions Coalition, a global network of over 250 civil society organisations, working to secure an international treaty to ban the use of cluster bombs. In another case the Fund, in partnership with The Children’s Society and Bail for Immigration Detainees, is seeking to influence the UK government to end the detention of children for immigration purposes. These aspects are represented in the “wider community objectives”.

Of course the charity needs to satisfy certain financial objectives. Like any other charity, the Fund needs to demonstrate financial prudence, efficiency and effectiveness in its operations and use funds. These, and other financial objectives, are represented in the financial perspective.

As might be expected the Fund’s three initiatives are at different stages of development and delivery. The campaign to increase the protection of civilians from the effects of cluster munitions and other explosive remnants of war is mature, with the Fund enjoying well established good relationships with key partner organisations. The work in palliative care is better developed in some Sub-Saharan African countries than others, so the Fund continues to develop an increasingly influential network of partners. The campaign for the rights of young asylum seekers is at an earlier stage with many of the key partnerships being developed. So, whilst each initiative is at a different stage of maturity of implementation, they are all delivering within the same strategy.

This can be seen in the overall Fund strategy which has three main themes: Maximising the unique assets of the fund, effective advocacy and being a good grant giver. Within these three themes the managers developed another level of detail that described what good practice and success was for the Fund as a whole. The emphasis that each initiative has in these three themes will vary, but each will be implementing a part of that strategy.

Beneath these major themes to the strategy, the Fund’s management identified a number of enablers of their strategy. On the simplified version of the strategy map these have been shown as improved skills, knowledge and culture. In the full strategy map these were specified in much more detail. Some transcending the Fund: others, depending on the maturity of their strategy, specifically applying to parts of the Fund and the strategy. Discussing and agreeing these led to the identification of opportunities to share knowledge and collaborate better within the Fund. This highlights how the approach creates conversations that add value to the organisation.

Finally, as with any charity, the Fund’s thinking, work and its strategy are underpinned by its core values and its mission: ”By giving grants to organisations, championing charitable cause, advocacy, campaigning and awareness-raising, the Fund works to secure sustainable improvements in the lives of the most disadvantaged people in the UK and around the world.”

The managers and their teams then developed the details of where their emphasis was within the overall strategy. They also detailed the characteristics of success. For instance, advocating for palliative care in Sub-Sahara Africa, results in different approaches in different countries as governments viewed the issue differently, some were more receptive than others. This focused the activities of that initiative manager and their team. Likewise, different types of partner organisations required handling and working with, in different ways: all within an overall strategy for the Fund.

Only once each initiative had developed its strategy map, from the overall framework, and was happy with it, did they start to detail the scorecard behind the strategy map. The scorecard detail provided them with the opportunity to set out the measures, targets, actions and responsibilities for each of the elements of their strategy. Now, there was detail as to how each of the initiative’s objectives will be delivered, together with any issues and an assessment of progress by the initiative’s manager. Overall this ensured a complete picture for the initiative, which could be viewed across the initiatives to get the overall picture for the Fund as a whole.

Learning from the process

The process of thinking through the strategy map and developing it, in itself helped the team at the Fund. This is very common as the approach encourages a more strategic view than is often taken with traditional balanced scorecards. Overall the work quickly produced a clear picture of the Fund wide strategy and what subsequent action was required. As a result, the consistent strategy became easier to assess despite different parts being in different stages of maturity.

One initiative used the approach to think through their strategy in more systematic detail. They used it as an aid to strategy development and thinking. This helped them detail and articulate their strategy far more clearly than they had before. Across the Fund, the common framework helped the initiatives create points of collaboration, conversation and improvement, where previously they were not as prominent.

From a financial and resource management perspective the approach helped them to assess the most effective, efficient and economic use of the Fund’s limited resources. For example, the initiatives were able to assess the most cost effective balance between grant making and other activities to achieve their objectives. The approach, being focused on objectives rather current activities, helped Fund staff to reconsider the process of strategy evaluation and make decisions objectively.

It took barely two months for the Fund to move from initial briefings to the development of the detailed scorecards for each initiative. Most importantly, this was achieved with minimal consultancy support. This was due to the consultancy approach used being designed to maximise skill transfer, understanding of the underlying principles and ownership. Thus it became “my strategy and scorecard”. After all they were the ones who would continue to use them to discuss and present progress on their strategy.

Operational use

Operationally the management teams review and update their strategic balanced scorecards every month with each of the three main initiatives reporting to the Board of Directors in detail every three months.

The two initiatives that were more mature and articulated their strategy in the strategy maps and strategic balanced scorecard continue to use their weekly task and deliverable lists for day to day management. However these detailed lists now operate in the context of the overall strategy, so it is easy to link through from the operational, day to day, detail to the overall strategy and larger objectives. For them the strategic balanced scorecard provides a broader context that informs, explains and reports their day to day activities. The range of objectives on the strategy map provides an agenda to ensure all aspects are covered each week.

The team that developed and articulated their strategy using the strategy map thinking are also using the approach for their operational, day to day, performance management. For them the approach is more embedded. They operate the balanced scorecard at a more detailed level and then abstract the essence of it for their board reporting.

Both approaches work for the initiatives. Both easily link to the overall scorecards and strategy maps. Most importantly, when there are discussions about the most effective and efficient use of resources across the Fund, it is far easier to asses the overall needs, common themes and look where improvements can be made across the Fund in the most cost effective way.

Presenting to the Board of Directors

An important role for the strategic balanced scorecard was to explain and present the strategy to the Board in a succinct and effective manner. The Board was given a comprehensive introduction to the new way of presenting the strategy, which has been very positive. The breadth of material and its natural structure has helped the managers quickly demonstrate the overall picture to the Board; it has allowed the Directors to get the wider picture and to focus in on areas that need attention. The Director Board feel more confident that they are seeing the bigger picture and can discuss detail as they wish.

Dr Astrid Bonfield, the Chief Executive of the Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Fund, has also found the approach valuable. “When I am preparing for a Board meeting I simply go through the three strategic balanced scorecards for each part of the Fund. Once I have done this I feel I am fully briefed to answer any questions about the detail within each area. It has made preparing for Board meetings much simpler, quicker and more effective. It also helps discussions with the initiative staff. This is a feeling every Chief Executive would want to have.”

On receipt of new reporting methods, many Boards often request more detail to be assured that they are getting the full picture. After a few meetings involving strategic balanced scorecard reporting at the Fund, the Board decided they were happy with less detail being provided and the initial reporting was simplified. This is a common cycle that Boards go through when experiencing the strategic balanced scorecard for the first time: at first, more detail is required, in assurance that managers are providing the bigger picture. The level of information presented is reduced, once Boards are confident that the detail is available and that things are running smoothly. The strategic balanced scorecards assure the Board that they can access more or less detail as they wish.

Taking a wider view, all the Fund’s initiatives operate in dynamic external environments where external forces may either invalidate or even achieve the Fund’s objectives. It is therefore necessary (as it should be in most organisations) to assess the continuing validity of the strategies employed and the objectives to be achieved. A measures based approach did not allow this. The modern balanced scorecard and strategy map, however, provide a clear and concise framework in which to do this. It is easier to explain what has happened and easier to refine the strategy as a result.

Conclusions

A year after the introduction of the balanced scorecard approach, how is it working out?

As John Roche-Kuroda, Head of Finance at the Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Fund says, “The process of developing strategy maps and modern balanced scorecards has provided a framework in which to articulate and develop strategy. The process provided a clear overview of how various strategies within the individual initiatives as well as across initiatives ‘interacted’; and how different strategies developed to achieve different objectives had various aspects that were complementary. It helps us ensure the most effective, efficient and economic use of resources.”

Some of the managers have fallen in love the approach. Others see it as a practical tool that helps them manage and deliver. It has found a natural level in the organisation. On one side sitting above the day to day detail, to which it provides a context. On the other side being a tool to articulate the strategy, show how the different initiatives are implementing that strategy and informing how the strategy should evolve and develop.

It is informing Board discussions, helping managers manage and making the life of the Chief Executive easier. In its way it is contributing to the Fund’s effective use of its money, thereby ultimately helping the beneficiaries of the Fund and contributing to a world where the rights of the disadvantaged are respected.

Phil Jones, Managing Director Excitant Ltd.

John Roche-Kuroda, Head of Finance, The Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Fund.

About the Authors

John Roche-Kuroda is Head of Finance at the Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Fund.

Phil Jones is Managing Director of Excitant Ltd. He worked for the originators of the Balanced Scorecard between 1996 and 2000 and now runs Excitant Ltd which specialises in Strategic Balanced Scorecards. He is also author of “Communicating Strategy” published by Gower in 2008.

Download this case study as a pdf of this balanced scorecard case study for a charity